Let’s dive into argument systems - particularly SNARKs.

Taking a Peek

First let’s get an overview of how SNARKs work at a high level. We will identify different components involved when performing a SNARK but keep them abstract for now.

Arithmetic Circuits

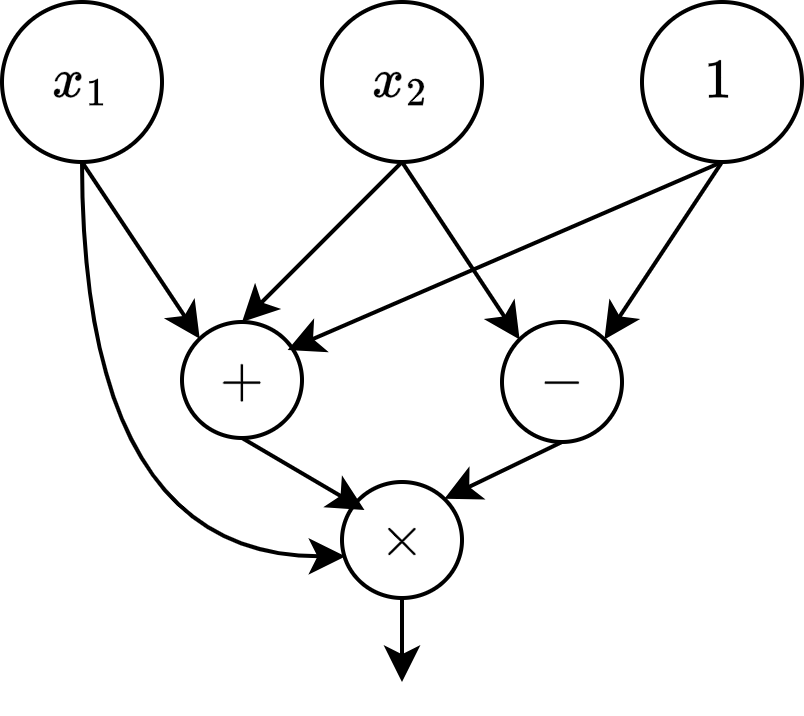

An arithmetic circuit is essentially a computation graph of a formula. Let’s assume we want to compute \(x_1 (x_1 + x_2 + 1) (x_2 -1)\). Now, the computation graph gives us the recipe to compute this formula. In crypto, we usually do the computation in some finite field \(\mathcal{F}\). So the graph essentially gives us an evaluation recipe to compute some function \(\mathsf{C}: \mathcal{F}^n \rightarrow \mathcal{F}\), which usually describes the evaluation of a polynomial. The computation graph for the above formula is given here:

We have our initial input nodes, which are \(x_1\), \(x_2\), and \(1\). And we have our “operation nodes” - our gates. The size of the circuit is given by the number of gates, which is 3 in our example (\(|\mathsf{C}| = 3\)).

Arithmetic circuits are important elements when building an argument system. Usually, a prover wants to prove that he knows (part of the) input which leads to a certain circuit output. For example, he might want to prove that we know the input to a hash function for a given hash value. We would build the corresponding arithmetic circuit corresponding to \(\mathsf{C}_ {hash}(h,m) = (h - \mathsf{SHA256}(m))\). The arithmetic circuit can be built with roughly \(20K\) gates, i.e., \(|\mathsf{C}_{hash}| = 20K\).

Argument System

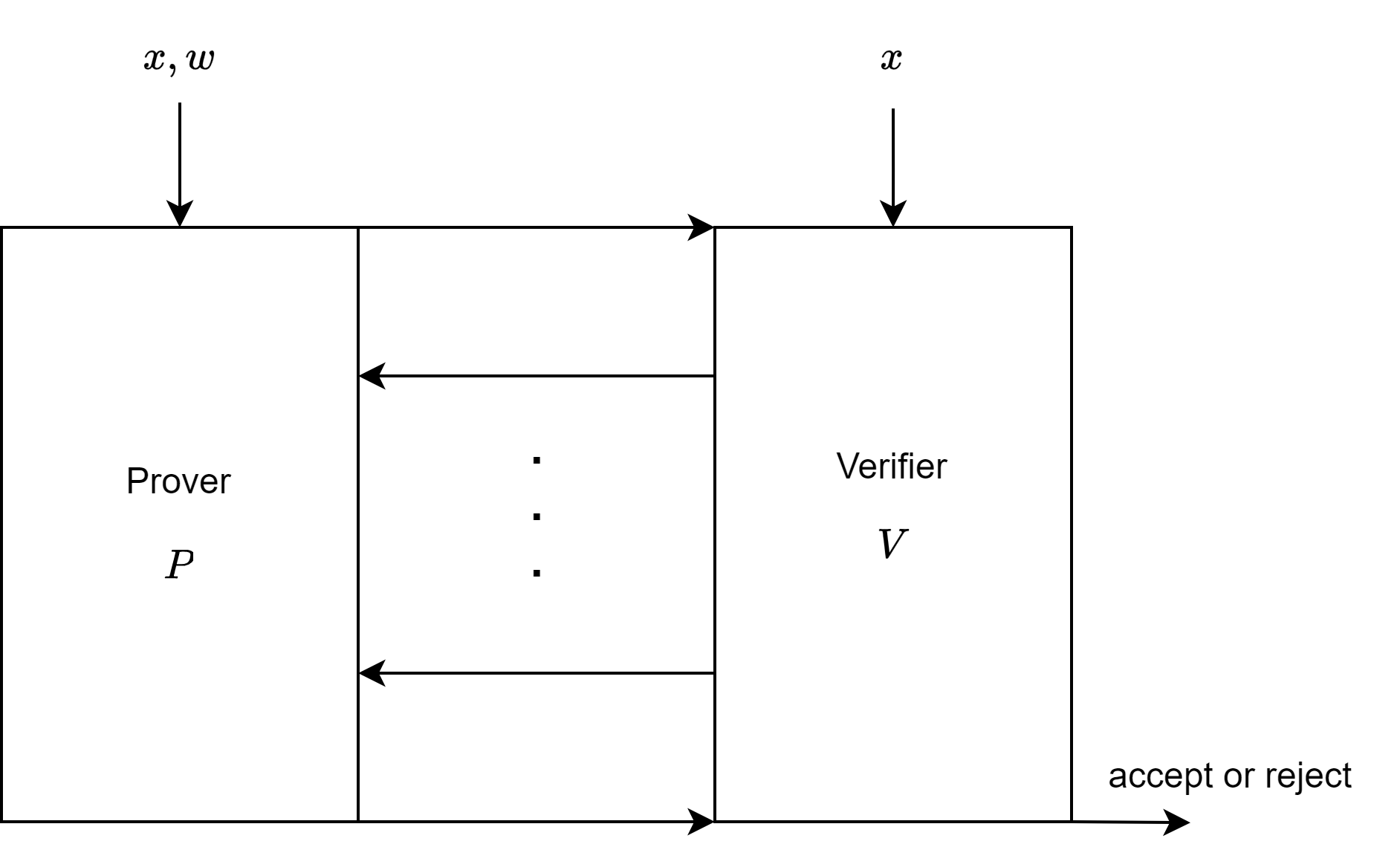

The input to the circuit is divided into a public statement \(x \in \mathcal{F}^n\) and a secret witness \(w \in \mathcal{F}^m\), such that \(\mathsf{C}(x,w) \rightarrow \mathcal{F}\). The prover gets both \(x\) and \(w\), while the verifier only gets \(x\). Now, the prover and the verifier exchange messages, and at the end, the verifier must be convinced that there actually is a witness such that \(C(x,w) = 0\).

(Non-interactive) Preprocessing Argument System

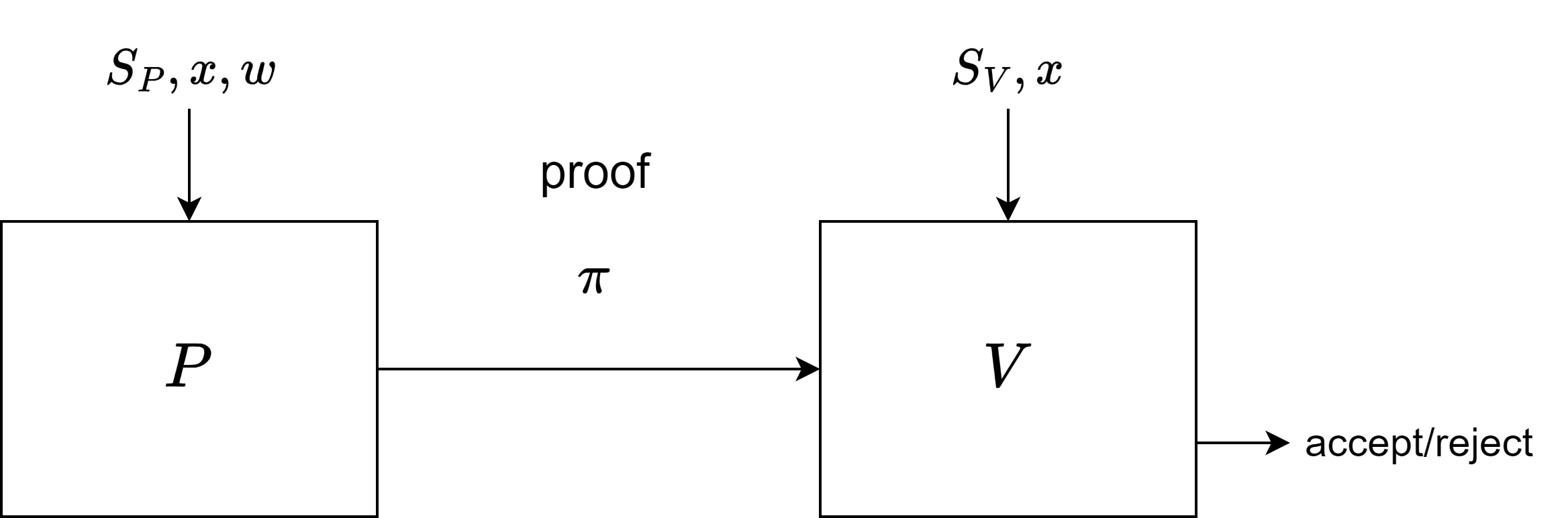

In some cases, we want to keep communication between the prover and the verifier to a minimum. We’d like the prover simply to produce a proof that he has a witness \(w\), and based on this proof, the verifier will accept or reject:

In this handy case, where no communication is needed between the verifier and the prover except for sending the proof, we have to build additional public parameters through a setup function. This setup function \(S\) takes the arithmetic circuit as input and outputs a tuple of public parameters, i.e., \( (S_P, S_V)\leftarrow S(C)\). \(S_P\) will be used by the prover to generate the proof, while \(S_V\) will be utilized by the verifier for verification of the proof. Broadly speaking, \(S_V\) is essentially a short “summary” of the circuit. So, a preprocessing argument system is the triple consisting of the setup function \(S\), the prover \(P\), and the verifier \(V\).

Completeness

There are some requirements an argument system must fulfill. We will omit the formal definitions here but rather give intuition for them. The first one is called completeness and is rather straightforward:

\(\forall x,w : \mathsf{C}(x,w) = 0 \implies Pr[V(S_V, x, P(S_P, x, w)) = \text{accept}] = 1\),

basically saying if \(\mathsf{C}(x,w) = 0\), an honest verifier will be convinced by an honest prover that there actually is a witness \(w\).

Knowledge Sound

If the verifier \(V\) accepts, it is certain that the prover \(P\) “knows” a corresponding witness such that \(\mathsf{C}(x,w) = 0\). I put “knows” in quotation marks because we haven’t defined what knowledge means in cryptographic terms, and we won’t. I think the intuitive understanding of knowledge (in the sense of the amount of information) is enough here.

Optional: Zero Knowledge

All public parameters \((\mathsf{C}, S_P, S_V, x, \pi)\) reveal nothing about w.

Succinct Preproccessing Argument System (SNARK)

A succinct preprocessing argument system (finally, we learn what a SNARK is) is a preprocessing argument system where the proof is short and the verification process is fast, i.e., \(\text{size}(\pi) = \mathcal{O}(\log(|\mathsf{C}|, \lambda))\) and \(\text{time}(V) = \mathcal{O}(|x|, \log(|\mathsf{C}|), \lambda)\), where \(\lambda\) is called the security parameter of the system.

Now, the famous zk-SNARKs refer to SNARKs that are Zero Knowledge as defined above.

This is essentially a brief summary of module I of the whiteboard sessions at zk hack. Go check it out!.